Description

|

978-1-923006-46-1

|

Softback

|

|

978-1-923006-47-8

|

Hardback

|

|

978-1-923006-48-5

|

Epub |

|

978-1-923006-49-2

|

PDF

|

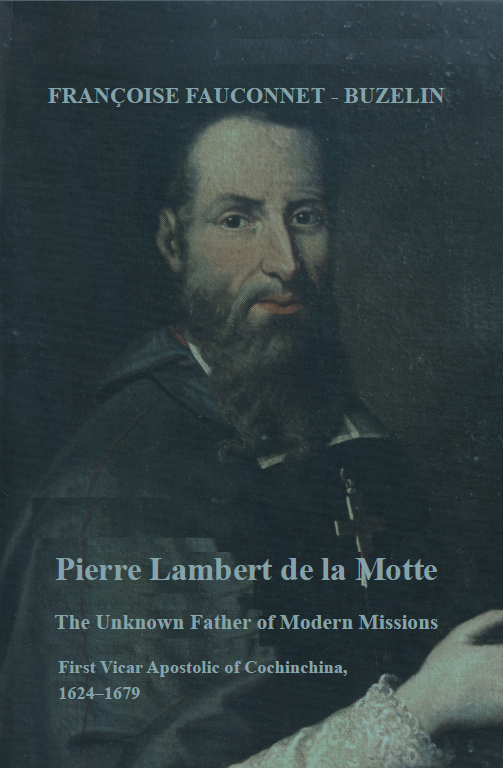

Address at the launch of Françoise Fauconnet-Buzelin

Pierre Lambert de la Motte: The Unknown Father of Modern Missions: First

Vicar Apostolic of Cochinchina, 1624–1679

Translated by Father Jefferies Foale CP

Vietnamese Catholic Community, Pooraka

6 April 2024

During the last forty years the Christian Church in Australia has been reinforced in numbers and vigor by thousands of Christians from Asia who have come to live in this country. In many places those congregations that are growing and flourishing are those which have been augmented by keen Christians from Vietnam, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, India and Sri Lanka. But most Australian Christians have very little knowledge of the history of Christianity in Asia, apart from a vague and inaccurate idea that it was brought by European colonial powers in the nineteenth century. Very few realise that Christianity has a long history in Asia, going back in some places to the early centuries of the Christian era, carried by traders through the Persian Gulf. Some may have heard of the Jesuit mission to China in the seventeenth century which looked promising, then was stamped out. But the early presence of Christians in other counties in Asia is less widely known. The beginnings of the Catholic Church in Vietnam go back to the sixteenth century.

This biography of a great French missionary Pierre Lambert de la Motte is an important contribution to our knowledge of this early period. The author, Francoise Fauonnet-Buzelin is a historian who was commissioned for this task by the Paris Foreign Missions Society and therefore has been able draw upon its archives. This is a reliable account that will be a standard work for many years. Happily, we now have access to it in English translation through the work of Father Jefferies Foale who has worked in Vietnam for eighteen years and has a deep knowledge of its church. The translation of a book of this size was a huge project. Father Jeff’s work will bring the story of Bishop la Motte to an international readership and to specialist libraries around the world.

In the nineteenth century accounts of missionary work and biographies of famous missionaries were hugely popular. Devout people loved to read about the expansion of Christianity and its heroes and missionary martyrs. Thousands of books were published about them and were given as prizes in Protestant Sunday schools. By contrast, the history of Christian missions and biographies of missionaries are not popular topics these days. Missionary activity is often portrayed as hopelessly entangled with European imperialism and blamed for the destruction of indigenous cultures. This hostile view is widely accepted but it’s mostly wrong. Historians are now looking at Christian missionary activity with new eyes and a more balanced view is emerging.

In brief outline, Pierre Lambert de la Motte was born in 1624 into a prosperous and pious family of the lesser nobility in Normandy. The first half of the seventeenth century was a golden age in the Catholic Church in France. It produced great saints such as Vincent de Paul, Francis de Sales, the religious philosopher Blaise Pascal, and many others. Young Pierre became a lawyer, then a magistrate – was doing well. Then in 1654 he underwent a religious conversion and began a new way of life – he wanted to renounce all. He entered an intense and ascetic spiritual life, based on prayer and fasting. He decided to become a priest, was ordained in 1655 and volunteered to go to Asia as a missionary. He was one of the founders of a society of secular priests called the Paris Foreign Missions Society.

The background was this. For over a hundred years Catholic missionary work in Asia had been entrusted by Rome to the kings of Spain and Portugal. The Jesuit order, founded in 1540, sent missionaries to China and Japan and looked after its own interests. Missionary work in the East was chaotic and riven with rivalries. Very little evangelisation. Few local clergy were ordained. The Church had no missionary strategy. Then in 1622 Rome created the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, the official missionary department of the Catholic Church. This was to mark a new beginning in Catholic missionary strategy – clear instructions and under Roman control. Out of this came the Paris Foreign Missions Society which sent Pierre Lambert and other missionaries to South-east Asia.

In 1658 Pierre Lambert de la Motte and Francois Pallu were appointed as vicars apostolic (missionary bishops) for south-east Asia: la Motte as Vicar Apostolic of Cochinchina (titular bishop of Beirut), Pallu as Vicar Apostolic of Tonkin. Bishop la Motte’s vicariate embraced southern Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand. In 1659 Rome issued official guidelines for the missionaries – ‘the Roman charter of modern missions’.

The Catholic Church had already been planted in Vietnam by a great missionary, Alexandre de Rhodes, who had been expelled in 1645 after an edict banning Christianity. The two bishops set out separately in 1660 – a long and perilous overland journey through Syria and Bagdad. They made their base at Ayutthaya in Siam (now Thailand). This was then the capital of Siam – a century later it was destroyed by an invading Burmese army and is now a famous ruin. While at Ayutthaya they two bishops held a synod which drew up what we would now call a policy document, expanding the Roman instructions. It was not until the 1670s that Pierre Lambert was able to visit Vietnam. He died in Siam in 1679, aged 55.

In reading this book I am struck by many themes that recur in histories of Christian missionary work throughout the world.

- The complex relationship of missions to European colonial powers. Colonial governments often wanted to use Christian missions – and sometimes to block them – for their own ends. Some missionaries were keen to associate themselves with colonial government and its policies – saw it as a protector, or their only protector in a difficult environment. In this period Asian rulers easily saw missionaries as agents of European powers – the Portuguese, the Dutch, the French – which were seeking to increase their influence in the region. Many missionaries were wary of entanglement with colonial ambitions and sought to keep their distance. Bishop la Motte was one of these. But even he and the Paris Foreign Missions Society were in the end overwhelmed by the politics and received financial and other support from King Louis XIV of France.

- Rivalry between missionary organisations. In the nineteenth century this was usually Catholic versus Protestant as each group tried to out-manoeuvre the other. In this account, however, the fighting is between Catholics. It is not edifying. We read of the amazing hostility of the Portuguese priests in India and also the Jesuits towards the newly arrived French missionary priests who wanted to keep them out of their preserve. And we read harsh criticisms of the Jesuits – lax, exaggerated their achievements, arrogant, involved in business and greedy for money, unwilling to cooperate with others, ‘incorrigible cheats’. Bishop la Motte was very critical of the Jesuits and they in turn blackened his name and accused him of abuse of power and much more.

- Encounter with other religious traditions. Missionaries who journeyed to Asia met for the first time in their lives adherents of religions that they believed were false and idolatrous. However, they had to learn about these religions in order to convert the people. In the process they were often surprised to find that people they believed were sunk in thick darkness displayed a sincere piety and that Buddhist monks lived an austere way of life with a high moral intent. Bishop la Motte respected what he saw– the devout practice of their religion – without accepting it as in way true. Of course this is a long way from modern interfaith dialogue but it was a start. And it raised big questions such as: were all the followers of the great Eastern religions doomed to everlasting punishment? Did these faiths contain some light that came from God?

- Accommodation with indigenous culture and traditions – inculturation, formulating Christianity in ways that penetrated and fitted the local culture. Missionaries varied greatly in their approach. The Jesuits were at the cutting edge on accommodation but their tolerant approach was debatable. Their critics thought they had given too much away and had not stressed the distinctives of the Christian message and way of life: that this necessarily involved a break from the past, a conversion of the heart. In this book we read about a difference of opinion in the 1670s over whether missionaries in a Buddhist society should abstain from meat and become vegetarians. The question of inculturation and accommodation to the local culture, and what it involves, is a continuing area for debate and discussion among missionaries of all Christian traditions. Bishop la Motte and his fellow missionaries were into it from the first.

- Building a church. Converting people to Christianity was the first step. The next was to build an indigenous church with its own clergy. This was often a difficult process. Some missionaries thought it would take many years before local Christians could be trusted to lead the church. For Catholics this involved selecting young men of promise to enter seminaries where they would be trained for a celibate priesthood to celebrate Mass and administer the sacraments in Latin. These early French missionaries in Vietnam were forward-thinking. They believed that the creation of an indigenous clergy was the only way the Catholic Church would take root and survive. Bishop la Motte in 1665 started a seminary in Siam where young men who had been catechists in Cochin China and Tonkin would be trained for the priesthood. The first Vietnamese priest was ordained in 1668. Many others followed.

- The importance of particular leaders who made their mark. One of them is Alexandre de Rhodes. Bishop la Motte is another. He emerges from this book as a man of passionate views – combative, determined, uncompromising, difficult to work with. He was effective but he created enemies. As a result, he has been written out of the history of the Vietnamese Church. But the Church needs people like him.

Bishop la Motte had courage, drive and vision. He was a man of deep spirituality, and he was a great organiser. Along with Francois Pallu, he laid the foundations of the Catholic Church in Vietnam and he deserves this fine biography. I congratulate Father Jeff for bringing the remarkable life of Pierre Lambert de la Motte to the English-speaking world and ATF Press for publishing it.

Dr David Hilliard OAM